Are you looking to get off the beaten path or just pedal around the neighborhood? There's no better vehicle than a mountain bike to tackle a variety of terrain. Do you dream of riding remote trails deep in the backcountry, taking hot laps on the dirt paths in the park, or something in between? There's certainly a mountain bike that can do it, and do it well. The technology is rapidly evolving; full-suspension mountain bikes, once the realm of the the MTB elite, are becoming ever more affordable and common. Looking for a ride specifically for women or for a specific trail? There are plenty of choices. If you still have questions, stop by the shop, shoot us an email or give us a call. We're here to get you on a bike that fits your needs. After all, the best mountain bike there is? That's the one you end up riding home.

Mountain bikes are complex machines with many parts. The frame, wheels, fork, tires, crank, cassette, and pedals can all impact how the bike will ride. We won't get into every detail, but here's an overview of a mountain bike's main components.

Drivetrain

The most common gearing options in the mountain bike world are 2 or 3 chain rings paired with a wide-range 10-speed cassette. The chain is shifted from cog to cog using a front derailleur over the crank and a rear derailleur by the cassette. Value-minded bikes will have fewer cogs (or speeds) on the cassette. A drivetrain with 2 chain rings and 10 cogs on the cassette will have 20 speeds (2 x 10). Additional speeds on a cassette create smaller gaps between shifts: say you're pedaling up a hill and your legs are starting to burn, a downshift on a 10 speed cassette will be less noticeable than a downshift on a 7 speed cassette. The newest trend for drivetrains is a single chain ring paired with an extremely wide-range cassette. This saves weight, reduces complexity, and gives you almost the same range.

Wheels

Weight, hub engagement, and rim width all have a massive impact on how well a bike performs. With advances in carbon fiber, aluminum extrusions, and the rise of disc brakes, rims are getting lighter, stronger, and wider. A lighter rim decreases the rotational mass of a wheel, making it easier to accelerate and change direction. Another factor to consider is rim width. Wider rims give tires more support while cornering, and change the shape of the tire to improve traction. The last thing to consider when looking at wheels is rear hub engagement. Engagement is how many degrees the cassette can turn before it drives the wheel forward. In technical terrain, a smaller degree of engagement allows you to keep your pedals where you need for quick power.

Brakes

Modern mountain bikes use disc brakes to deliver excellent stopping power and control in a wide variety of conditions. A brake lever actuates a caliper; pistons in the caliper compress the brake pads on to the rotor which, in turn, slows the wheel. There are two types of disc brakes: mechanical and hydraulic. Mechanical brakes use a cable to actuate the caliper. These brakes are are easy to service, and work great in cold temperatures. Hydraulic brakes use hydraulic fluid to actuate the pistons, just like you would find in a car or motorcycle. They have more stopping power and better lever feel, or modulation, than mechanical brakes. They do require a bit more maintenance and periodically must be "bled" of air, for optimum braking performance.

Suspension

Mountain bikes come in three flavors: rigid (no suspension); hardtail (suspension up front but not in the back); and full suspension (suspension front and rear). Suspension provides a smoother ride, increased control, and improved handling. The downside is that suspension components add weight.

Lower-end suspension is often nothing more than a coil spring and a rudimentary damping circuit that controls pre-load and rebound. More sophisticated suspension systems use air springs and give you more adjustments to control and change how it reacts as you roll over bumps, rocks, and ramps. Usually the more expensive the suspension component, the better performance you will experience.

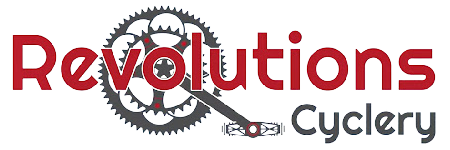

Suspension is measured in millimeters of travel. For example, you might see that a fork has 100mm of travel. This translates to about 4 inches. Suspension travel in a fork is a measurement of how much the lowers slide up and down the stanchions. Suspension travel in a frame is determined by the layout and design of the frame itself. More travel translates to a more capable suspension system.

Disciplines

Cross Country

Cross Country contains the widest variety of mountain bikes, though they are predominately focused on speed and climbing ability. They range from entry level value-spec'd hardtails to ultra-light, full-carbon World Cup race machines. A cross country bike is built to be light and efficient: usually featuring around 100mm of suspension travel and quick-handling geometry. Cross country bikes climb very well, but are often not the most confident descenders.

Trail

Trail bikes sit in the Goldilocks zone of the mountain bike world. Their 120-140mm of suspension travel is not too little and not too big. Trail bikes can be either full-suspension or hardtail, and feature more relaxed frame geometries to balance climbing with descending capabilities. Most full suspension bikes fit firmly within the trail designation. They ride well in most locations, but might feel outgunned in more technical terrain.

All-Mountain

All-mountain bikes are the rowdy, loud, and aggressive big brothers of Trail bikes. With 140-170mm of suspension travel and slack geometry that's more suited for ripping down hills than going up them. That's not to say these bikes can't climb. Some all-mountain bikes are excellent climbers, but they are still more focused on speed and descending. They are most commonly full suspension, but there are a few rare hardtails that fit this category.

Wheel Size

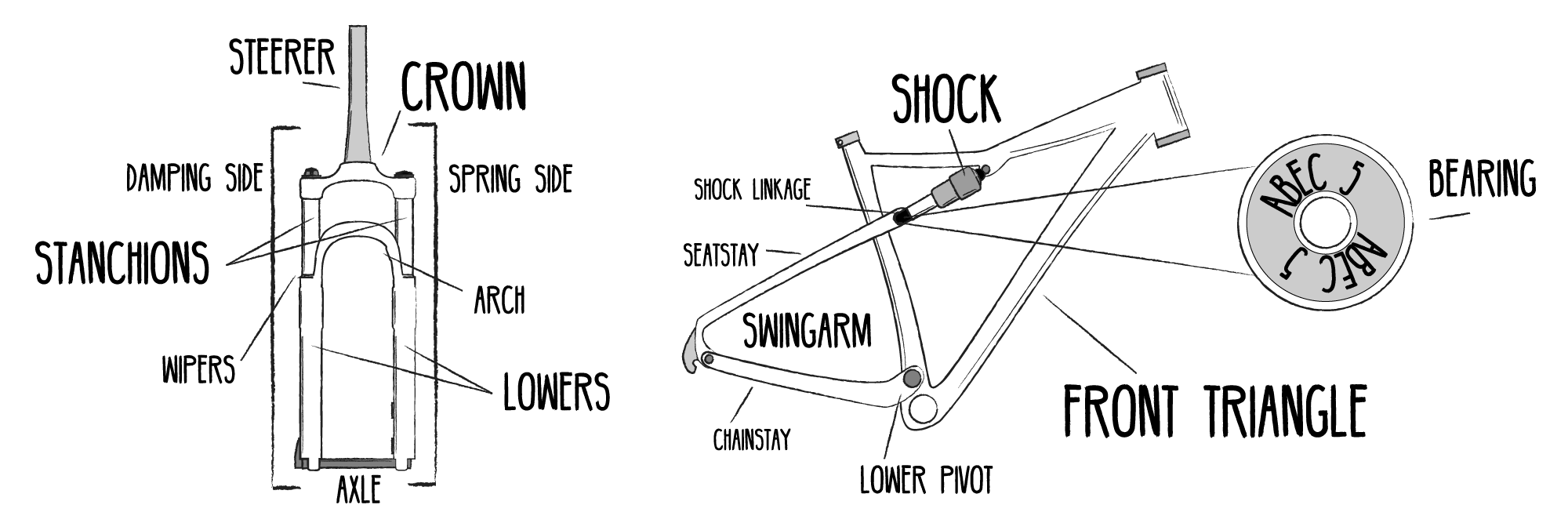

Wheel size will be one of the most important variables to look at when shopping for a new mountain bike. Currently, the most common sizes are 27.5 (650b) and 29-inch wheels. In the past, mountain bikes all ran on 26-inch wheels. Standards have since given way to several wheel options. After the widespread adoption of 29-inch wheels in the late 2000’s, manufacturers started to look at wheel size to make performance gains. 27.5 emerged as a great compromise that balances most of the maneuverability of their 26-inch cousins, but delivers much of the efficiency and technical ability of the 29-inch wheel size.

Fat Bikes and Plus Bikes

The mountain bike world has been seeing a trend toward seriously big rubber. Fat bikes have been around for a few years and have proven that they are capable and fun in many conditions, not just snow, sand, and slop. Another big trend has been toward plus-size tires, or tires that aren’t quite wide enough to be considered fat bikes. Below, we’re going to break down the differences between these two chunky options.

Fat Bikes

Fat bikes are the monster trucks of the mountain bike world. Their enormous tires (around 4-5 inches) go just about anywhere. Big tires deliver amazing traction and a fairly smooth ride. Most fat bikes are designed to get off the beaten path, and the component choices reflect that. Expect to see parts picked for durability over weight in this category. Fat bikes require a very specific set of specialized componentry like wider hubs, rims, and bottom brackets, so parts may be a little less common.

The biggest differentiating factors when buying a fat bike are tire width and geometry. Some fat bikes run the biggest tires possible and have a more upright geometry for stability in snow and other lose surfaces. Other fat bikes are built more like a cross country or trail bike, along with skinnier 3.8 or 4 inch tires. These bikes rip up lose dirt and hardpack and are great in warmer months. Most fat bikes are rigid, but suspension forks and even full suspension bikes are becoming more popular.

Plus Bikes

After the advent of Fat Bikes, a few manufacturers began exploring the advantages of slightly wider tires in more traditional applications. Plus Bikes feature tires around 3-inches. The wider tires deliver incredible grip, a smoother ride, and supreme versatility. The plus size or mid-fat tire doesn’t add as much weight as a fat tire, and can utilize many of the more standard mountain bike components.

Plus bikes bridge the gap between standard and fat and are just now starting to see more widespread adoption. A hardtail with a suspension fork has been the most common variant, but some manufacturers are producing full suspension plus bikes. Two major varieties are starting to emerge; 27.5+ and 29+. Just like their narrow-tired counterparts, the 29+ version rolls more efficiently, while the 27.5+ variety is more playful.

v